Recent Posts

do you have faith in Bhagvad Gita ?

Is Indra considered the Supreme God In vedic hindu...

Opinions on Picrel

How do I worship Dyaus Pitr?

Opinions ?

Some artwork I made using AI

Opinions on Rasa Panchadhyayi ?

indranons zara idhar aana

Which sect are you most attracted to ?

Who is your isht Devi/devta?

Caste is a Western Construct ....

Does God Exist?

Hindus are doomed

Varnashrama

What is that "One Book(s)" that everyone should re...

Post Indian normiecore

christianity

watch this jain baba bragging about jains exploiti...

Why do Chintus celebrate Brahmahatya ?

To all my Musleem Bhachanners

As a Dalit I envy the feeling of religiosity among...

Ashwamedha Yagya

some betichods who sold the religion for cheap rew...

If a muslimahh ties you rakhi should one assume sh...

help with mujeet spreading propaganda

Discourse on the Upaniṣads

B-bros

Yaar Pajeet

coping seething dilating

was Vritra really a serpent ? In my opinion it was...

systematized Theology anyone ?

Kindness will save the world

somebody explain me this mental illness of worship...

Hercules: The Lost Jat of Antiquity?

sNzBUm

No.99

For centuries, the myth of Hercules—the indomitable Greek demigod—has been a cornerstone of classical Western mythology. Known for his immense strength, his twelve labours, and his ultimate ascension to divine status, Hercules has been immortalized in art, literature, and folklore across civilizations. However, a groundbreaking reassessment by linguists and historians suggests that Hercules, far from being merely a Greek hero, may have his origins in the martial traditions of the Jats of India.

Recent studies in comparative linguistics, Indo-European migrations, and ancient historiography reveal striking similarities between Hercules and figures from Jat folklore and history. The warrior ethos, the indomitable spirit, and the near-mythical strength attributed to Hercules resonate with the ancestral characteristics of the Jats, a traditionally martial community spread across northern India.

Linguistic and Historical Parallels

Linguists studying Indo-European philology have noted phonetic similarities between ‘Hercules’ and names prevalent among ancient Indian warriors. Some scholars argue that Hercules could be an Indo-Greek adaptation of ‘Hari-Kula,’ meaning ‘the lineage of Hari (Vishnu),’ a phrase often associated with Kshatriya clans, including the Jats.

Ancient Greek records also offer intriguing clues. The Greek historian Arrian, in his Indica, mentions a powerful warrior race in the Indian subcontinent whom Alexander the Great found particularly formidable. These warriors bore striking resemblances to the mythologized Hercules—massively built, fearless, and known for their wrestling prowess. Similarly, Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to Chandragupta Maurya’s court, wrote of an Indian Hercules-like figure, linking him to the region corresponding to modern-day Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh—strongholds of Jat heritage.

The Jats: Heirs to Hercules' Legacy?

The Jats have long been recognized for their warrior traditions, their legendary resistance against invaders, and their self-sufficient, agrarian yet fiercely independent culture. Could it be that Hercules was not a Greek invention but rather an adaptation of an older, Indic warrior archetype?

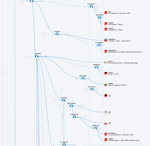

This theory gains credibility when one examines the broader pattern of Indo-Greek cultural synthesis. The post-Alexandrian era saw extensive interactions between the Greeks and Indian warrior communities, particularly in regions where Indo-Greek kingdoms flourished. It is possible that stories of Jat warriors, passed down through generations, were absorbed into Greek myth, transforming an Indic strongman into the demigod Hercules.

Revisiting Ancient Identities

The implications of such a revelation are profound. It challenges the conventional Eurocentric framing of mythology and compels scholars to acknowledge the fluid exchange of legends across cultures. If Hercules indeed has Jat origins, it reaffirms India’s role in shaping global mythological traditions and underscores the enduring martial legacy of the Jats.

Of course, much work remains to be done. Historical reconstructions require rigorous evidence, and while linguistic and anecdotal correlations are compelling, more archaeological and textual research is necessary. Yet, this emerging perspective invites us to look beyond simplistic historical binaries and embrace a more interconnected view of our shared past.

Could it be, then, that Hercules—the lion-hearted, the unconquerable—was not merely a Greek hero but a lost son of Bharatvarsha? The evidence, though still debated, suggests that the tale of Hercules may have begun long before Greece, in the rugged heartlands of northern India, where warriors still uphold his legacy.

toOedE

No.160

>>99(OP)

>Unironically asking if Hercules was Jatt Or Not.

No anon, Hercules Jat Nahi Tha. Jatta di kaun hi na thi us samay me. I say this in the nicest way possible, please stop being a massive faggot.

Any and all linguistic similarities between PIE chain languages like Greek and Indo Aryan ones are either coincidence or a given due to both evolving from same language.

Warrior Spirit is a given among half the planet earth because it was the only means to survive in the first place. Hercules itself is a wrong name with the actual name being "Heracles" (Ἡρακλῆς).